On my bookshelves, I have 94 books and 58 journal editions about Bob Dylan. And there are people who would consider this a paltry collection – mine only representing a small proportion of the total publications about this major but enigmatic cultural icon!

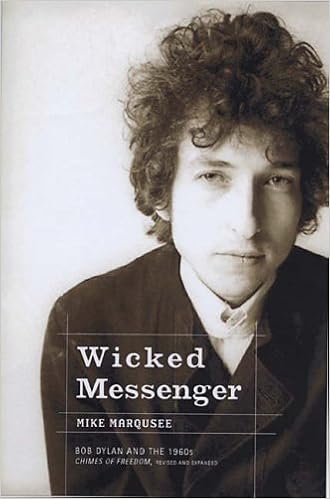

Leaving aside trivial attempts to cash in on interest in Dylan, the plainly ill-conceived, the content-less and the downright inaccurate, the universe of these publications tends to fall into various categories – biography, critical analysis from literary or musical perspectives, the parallels between his work and that of other artists, including even the classical Greek poets and Shakespeare. Mike Marqusee’s ‘Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s’ focuses on Dylan in the 1960s, the decade with which the artist is most associated in the popular mind, although he draws on sources from far more recent times. More specifically still, he considers the ‘political’ context and contribution of Dylan’s work at that time.

I consider it to be among the half dozen from my collection that I have enjoyed the most.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, which straddled my 16th birthday in 1962, terrified me – and the world. The Civil Rights movement, the heroic struggle to end racial segregation in the USA, beamed footage of an undeniably moral crusade onto our TV screens. And, within another year or two, the huge and awful destruction and loss of life in the Vietnam War was presented to us daily. In this febrile atmosphere, Dylan’s best work, songs from a youngster barely out of his teens, shone out.

In lazy commentary, the Dylan of this period is served up as a naive ‘protest singer’ who morphed into a drug-addled obscurantist, possibly by cynically exploiting the huge hunger felt by the young for a better, saner and safer world. Marqusee brilliantly reminds us of the incredibly mature, nuanced and human quality of the young Dylan’s best work – songs that still radiate artistic genius almost 60 years later. (I’m a bit of a fan!).

Various movements and causes tried to claim Dylan as their poster boy, tired hacks and commentators attempted continuously and unsuccessfully to stuff him into one of their cliched categories. And he held out against all the continual pressure, remaining an artist determined to follow his own direction. And, although never commentating directly or simplistically on matters ‘political’, he created a brand-new art form that captured perfectly and with great originality, the struggle for any individual in a society like the USA attempting to retain ‘authenticity’ – to live genuinely and seek truth in relationships – and with oneself. Then – and now.

Marquesee’s book takes us straight back into that tumultuous world, a time of great social progress, psychological and spiritual growth, daft fads and horrific atrocities. And he illustrates once again how ‘a strange young man called Dylan, with a voice like sand and glue’ (Bowie), created a body of work that dominated the cultural landscape – and will continue to do so for a long, long time.

11